Aguayo Homestead: A Glimpse of Pre-Railroad Days

The Aguayo family homestead was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on Dec. 28, 1995. The nomination was prepared by Jean Fulton and was accepted in the area of architectural significance. Although little remains of the many buildings that made up the homestead, it still stands as a testament to the self-reliance and resourcefulness of families living in Lincoln County, in this case in Tortolita Canyon near Nogal, at the turn of the twentieth century, as well as the influence of Hispano culture and the changes that took place after the railroad entered the area.

The Aguayo family homestead was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on Dec. 28, 1995. The nomination was prepared by Jean Fulton and was accepted in the area of architectural significance. Although little remains of the many buildings that made up the homestead, it still stands as a testament to the self-reliance and resourcefulness of families living in Lincoln County, in this case in Tortolita Canyon near Nogal, at the turn of the twentieth century, as well as the influence of Hispano culture and the changes that took place after the railroad entered the area.

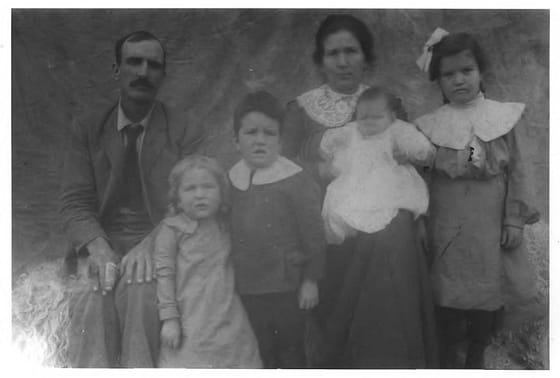

According to the nomination, Aristoteles H. Aguayo grew up during New Mexico’s days as a Territory. His family was from Mexico; his father ccame to the area and eventually was a certified teacher in Lincoln. Aristoteles was granted a homestead claim of 33 acres in 1912 through the 1906 Forest Homestead Act. He married Edith Sheppard and they had 13 children, 11 of whom survived into adulthood. Two died of flu.

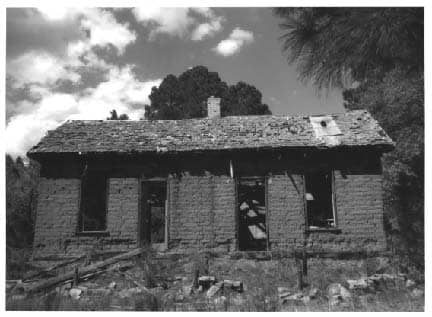

The homestead is made up of several buildings, built close together. A log cabin existed on the property already, and the family lived there while the main adobe house was being built. Mrs. Aguayo wanted her house to look like another home built in San Patricio by a carpenter from Mexico with the last name of Lara. The main house on the property is L-shaped with the intersection of the two wings facing south. It consists of three rooms. Other buildings and improvements include a bunkhouse, log chicken house, root cellar and underground apple storage building, wells, a double stall outhouse, a number of tilled fields and two garden plots. All the work was done by the family with the help of two men named Melquiades and Chavarria, also from Mexico.

The use of adobe in conjunction with wood, the shape of the house, the side gable roof with its two sections meeting at the center of the building and multiple doors are reflective of Hispanic-influenced architecture. In addition the fact that the adobe bricks were pre-formed rather than puddled as walls were built is also characteristic of Hispanic homesteads of the area.

Inside, adobe fireplaces aligned back-to-back were used to warm the front rooms. A single chimney of fired brick came up through the center of the roof. The floor and ceiling were made of tongue-and-groove wood, nailed onto thick wood joists with beaded wood mouldings hiding where wall, floor and ceiling come together.

Vestiges of trim exist on the outside. When the house was built, 1” x 6” boards were hammered into the wood frames with 4- and 8-penny nails to frame out openings. The roof was built with rough-hewn 2” x 4” lumber, first covered with metal and then wood shakes. A covered porch supported by log posts ran the length of the façade. The same 2” x 4” rough wood used on the roof was fashioned into headers over the windows that flanked the two doors under the porch and on either end of the building.

The family was dependent on the land for their livelihood. It was a physically demanding life filled with constant chores and extreme weather. They collected elder berries, wild lamb’s quarter and pinon nuts and hunted game. They were able to make some money by sending coyote, mountain lion and fox pelts to St. Louis to be made into fur coats. They ran over 125 head of Hereford cattle and raised hogs for sale, barter and personal consumption. All flat land was cleared with the excavated rocks used for erosion control. Carrots, cabbage, cucumbers, squash potatoes, onions and turnips were planted in addition to maintenance of orchards of grapes, plum, pear and apple trees, many of which, in addition to irises, still grow on the site. The property was protected by fences with juniper posts and barbed wire; some of which also remain.

Before the railroad, local materials were used. Stylistically buildings tended to be fairly plain and void of ornamentation. The Aguayos used rock and adobe bricks made from the local mud as well as timber that surrounded them but the metal roof, double-hung sash windows and paneled doors were most likely brought in by train. Even some of the fruit trees were ordered and sent via rail as were some of the home’s furniture.

Fulton noted in her nomination that this lifestyle was virtually gone within a single generation. Today the adobe of the Aguayo family homestead is crumbling, victim to the harsh weather conditions that plagued the family as well. The site is now on Forest Service land but exact location is not listed in the nomination. Fulton noted that the root cellar has been used as a trash dump and that graffiti and vandalism is present at the site. The inclusion of the site on the National Register will not stop the present from intruding on the past, but it does serve as a reminder of the lives of those who settled, worked and lived in Lincoln County many years ago.