“…And Now, Miguel” and the Partido System

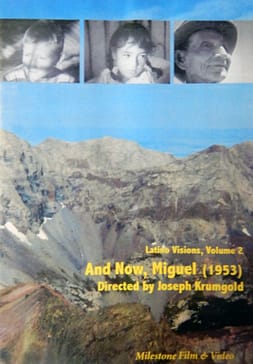

“…And Now, Miguel” (1953), directed by Joseph Krumgold, featuring the Chavez family, filmed in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and Los Cordovas, New Mexico.

Based on the Newberry Medal recipient for excellence in American children’s literature in 1954, the movie was made first as a U.S. Information Service documentary on the life of a shepherd family in northern New Mexico. Underlying the physical demanding job of tending sheep is the coming of age story of Miguel, the 12-year old son, who desperately wants to go with his father to the summer pastures high in the mountains. After praying to San Ysidro, the patron saint of farmers, Miguel earns his chance, but at a price paid by the entire family.

The movie was obviously done on a budget, but is important for its frank depiction of an area of New Mexico that has remained vehemently independent and more in line with its Spanish heritage than ta slice of modern-day life in the United States.

One vestige of the Spanish era that is broached in the film is the partido system when a wealthy patron would rent the ewes to local sheep herders. After a given period of time, the sheep herder would return the original number of sheep plus typically 20 percent, taken in the form of wool or lambs. While some landless sheep herders were able to build their own flocks, the cards were stacked against them through the use of contracts. Sheep herders entered into these contracts willingly and were able to access common land to graze the herd, but in such a harsh environment, the rate of sheep dying due to disease and/or predators was high. Often, sheep herders were forced to enter into more contracts to pay off the debt. The system, which on the surface, appeared to offer economic security and a means of subsistence living, could quickly turn into long-term debt servitude.

Peonage is not what “…And, Now Miguel” is about; it was meant as an educational tool to show the rest of America how some of its residents lived day-to-day. That it manages to capture a distinct culture, separate from so much of the country in such an objective, albeit paternalistic, way, makes this an important work in both New Mexican and Hispano history.